I can’t STOP TALKING ABOUT THIS ASSHOLE!

He’s not the only culprit this time. Buuuuuut he’s a dipshit, so let’s use him as an example. No, let’s make an example of him. That feels better. More right-er.

I’ve seen a tactic make the rounds lately, an anti-information, anti-intellectual tactic that I’m not a big fan of.

It’s the one in use when we say there’s an “Alphabet soup of committees,” in HHS. Like the committee that inspects the stuff you eat, or the bipartisan-supported one that tries to prevent domestic violence, or the ones who are actually working on chronic disease.

It’s the tactic that brings up stuff like:

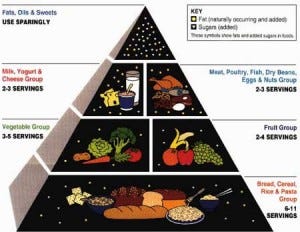

The food guidelines are “bloated,” “incomprehensible,” and “driven by the same commercial impulses that put Fruit Loops at the top of the food pyramid.”

Which, I mean, the food guidelines before RFK were 164 pages long, but the average person only really needs about 2 of those pages, which are broken up into 4 bullet points. The rest of the pages are just, you know, the evidence used to create those guidelines.

Oh, and, dumbass, Froot Loops ARE at the top of the Food Pyramid, which was retired in 2011, and being at the top of that pyramid means that a food should be eaten the least, not not the most.

I can see why that’s confusing, the top spot often being thought of as most prominent, maybe this is why they got rid of the food pyramid a decade ago, but, like, a tiny bit of information literacy really goes a long way.

Then we have the similar, “Processed foods have lots of ingredients I can’t pronounce.”

By the way, this is one ripped off from a goddamn ice cream commercial from the 90s:

BECAUSE IF YOU CAN PRONOUNCE IT, IF YOU CAN READ WORDS LIKE “SUGAR” AND “CREAM,” IT’S HEALTHY, RIGHT?

I can say, “A huge wad of cum,” so I guess that means I should be eating that on the regular. “All of my scabs,” is something I can pronounce with ease, so down the hatch!

Anyway, sensual indigestion aside, what I hear among these statements is the same, subtextual meaning:

I don’t know what all these agencies do, therefore they must be bad.

I don’t know what is in these pages of guidelines, therefore they are bad.

I don’t know what riboflavin is or how to pronounce it, therefore it is bad.

The Judge

One of the most frightening characters in literature, no doubt, is Blood Meridian’s The Judge. He’s just creepy as fuck. He is, basically, the devil. Like, the ACTUAL devil. It’s entirely possible he’s Satan, or a demon, or something.

And there’s a line he says that always summed him up for me:

Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.

There’s this creeping idea about information today, this concept that if someone doesn’t know about something, that something must be bad. If we don’t know about a thing, it’s because that thing is pulling a fast one on us, perhaps resulting in a desert-spanning wall of blood and carnage that is both awful and one of the greatest pieces of literature ever created.

Being like The Judge is not good, guys. He is not an aspirational character.

The Shit You Don’t Know

Things that you don’t know about are not inherently good or bad. YOU knowing about something, especially something outside your realm of expertise, probably isn’t a good test of whether that thing is healthy or unhealthy, safe or unsafe, a jam or a totally shitty song.

You not knowing something does not make that thing suspicious.

You not knowing something does not mean it’s useless.

It’s 2025. I Feel Like I Use That Section Heading a Lot.

I can understand how, in the 90s, people might be tricked into thinking things like their lungs can freeze when they run outside and it’s super cold.

But it’s 2025! And while that’s not always a phrase I end with an exclamation point, one reason to celebrate is that we have incredible access to information and huge numbers of people willing to explain things to us in understandable ways.

If you encounter something you don’t know, you can just fucking look it up. In seconds. Using the very rectangle you’re reading this on.

If anything, information should be seen as less hostile, less political than ever, because it’s readily available and trace-able back to the source in a way it hasn’t been before. It’s so much freer than ever.

Don’t Let Anyone Make Ignorance A Credential

I don’t know if there’s even much to say beyond that heading.

Don’t let anyone convince you of something by saying, “If this medicine was good for you, how come you’ve never heard of it?”

“If this dietary practice was good, why didn’t ancient peoples know about it?”

I think the best antidote to this sort of logic is to say, “Alright, let’s assume that this vaccine IS good for us, and let’s answer the posed question: Why didn’t ancient peoples know about or use it? Seriously, let’s talk about why.”

Ancient people didn’t know about vaccines because they didn’t know about life on the cellular level. They would have no way of knowing that delivery of a denatured or weakened virus would lead to an immune response because they wouldn’t know anything about any of the stuff I just said. They didn’t have microscopes. They didn’t have large swaths of data on responses to medicines. They didn’t have ways to test the chemical purity of a medicine.

I’m not shitting on ancient people. They built some cool stuff, including pyramids that may or may not have had Froot Loops at the top.

I think ancient people did the best they could with the tools they have available. And I suggest, rather than limiting ourselves to the things ancient peoples had available, we push to the limits of what we have available to us.

Why Don’t We Know Everything, and Why Is That Good?

In the book The Checklist Manifesto, Dr. Atul Gawande relates a story of early-ish aviation and a problem that came about when we started building more tech-infused planes that could drop bombs on stuff (hooray?): As planes got more complicated, it was harder to fly them. There was this switch to flip, that lever to pull, and god forbid you actuate the doohickey before you toggled the whatsagigjit. If you did that, boom, crash.

Pre-flight checklists prevented a lot of crashes and saved a lot of lives. Because while it’s important to check a lot of things, in order, to fly a bomber, it’s not necessarily important that one human knows all of those steps, memorizes them, and performs them correctly over and over with no cheat sheet.

This story isn’t really one that’s about checklists, it’s about the way we expand human knowledge.

If we all have to know everything, then we’ll all have a very shallow knowledge of a lot of things that just won’t be able to advance.

But if we can specialize a bit, create knowledge bases that don’t have to be for consumer-level use all the time, that allows us to move further.

If the engineer of a plane does not have to explain the physics behind flight to a technician, if instead they can create a checklist of things to go over and how to test them, that engineer can spend more time designing better planes and less time explaining the same basics to the world.

If, in order to study a vaccine, we had to reestablish the safety of mRNA vaccines every single time, it would impede our ability to manufacture new, effective, safe vaccines.

If, every time we created a food additive, it had to be something that every consumer, with zero background in chemistry or nutrition, was familiar with, we couldn’t really do much of anything with food. There would be no shelf stability, no ship-ability of foods.

We’ve advanced far enough that everyone knowing everything is not practical.

And this is good. It means we, as a species, know a lot!

But here’s the real kicker: Like I said before, the information, the ability to learn about just about anything, is available to you. If you are deeply concerned about AI, which you should be, you have the ability to learn about it. You have the resources.

The hard reality to face up to is that you can’t know everything because there’s too much to know now. Some fields, fields you don’t know a lot about, will advance beyond your understanding. They probably already have.

But you can push back. It’s just a matter of how you want to spend your time, what you think is most worthy of your attention.

Any way you look at it, though, it’s not worth your time to attack a knowledge area on the basis of it being “hard” or difficult for the layman to understand. Your time is better spent learning about something, anything.

Being Curious Is Better Than Being Certain

I guess I feel, when I see RFK smirk about not being able to pronounce ingredients, that we are in some pretty dark times. I mean, here’s a mouthful for you: Campylobacter, Yersinia, Brucella, Coxiella. That’s all stuff often found in a different mouthful, a mouthful of the raw milk you love so goddamn much, you dummy.

This isn’t about someone being unable to read. This is a well-educated guy appealing to everyone’s gut feelings, their sense that the world out there is big and scary and that it will run us over if we let it.

And in a lot of ways, the world IS that way.

At the same time, though, it doesn’t have to be.

When you come across something you don’t know, you can receive it as bad, as deceptive, as something hostile to you.

Or, you can act like an adult, assume you don’t know goddamn everything, and maybe look into it.