If you, like me, have been enjoying (in a “we’re doomed” kind of way) the recent congressional preceedings, then maybe you watched some of the talk between government lawmakers and AI companies.

It’s been…a trip, for sure.

I mean, not as embarrassing as grandpa asking if TikTok accesses home wifi networks.

And it’s not quite so “grade-schooler who didn’t do the book report as a lot of this stuff is”:

I guess it’s a bit more reasonable that people are confused by this stuff. It’s confusing.

So let’s talk it out, as I understand it.

What Happened

AI companies scraped what is, essentially, every book ever written, to train their AIs.

They probably didn’t scrape MY books, and if they did, I am so, so sorry. I really owe all of you an apology for what’s to come.

There have been a few different lawsuits, and results have been mixed, at best. Probably the best, fairest interpretation right now is that individuals are going up against AI companies and getting different rulings, depending on the specific situations and judges.

Why?

Because AI companies are citing Fair Use, and Fair Use is a lot more complicated than you think. It’s not just whether a specified amount of a work is used, not just about whether it affects a work’s market value, it’s A BUNCH of different factors put together. And there’s no objective measure for Fair Use, no one thing or even set of things you can do to guarantee Fair Use. A rights holder can still sue you for copyright violation, even if you go down the entire list of Fair Use factors and check every single box in favor.

In the 90s, Alice Randall wrote a book called The Wind Done Gone, which contained LOTS of elements of Gone With The Wind, and her publisher was sued. However, her publisher won because the courts decided that this was parody and acceptable Fair Use, even though it used very significant portions of the book.

On the other end, in Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprises, publisher Harper & Row sued The Nation for publishing a very teeny, tiny snippet from Gerald Ford’s forthcoming memoir, A Time to Heal. The problem? Harper & Row was planning to sell a whole lotta copies based on the world’s interest in Ford’s pardoning of Richard Nixon, which was contained in the memoir, and The Nation went ahead and published that snippet.

Tiny, teeny amount of the whole, but significant, and certainly had an effect on sales. This was not ruled Fair Use, ultimately.

You throw in the opaque fog of Fair Use on top of the mess that comes whenever government tries to make laws regarding cutting edge tech

And you don’t get a whole lot of solid, definitive answers.

The Case for AI, As I See It

Something I learned VERY early on in the library game is that most people suck at asking questions. They know what they want, or they think they do, but somewhere between ideation and expression, things change a lot. Early on in my career, I spent A LOT of time helping people answer a specific question only to find that the question we’d successfully answered wasn’t actually the question they wanted to ask.

You have to learn to ask questions, of the question-asker, before you just start typing.

I literally read a book about interrogations to try and shortcut this process. I thought, I don’t know, that I might be able to pick up on non-verbal cues or some crap like that. But the problem with trying to use interrogation tactics is that I can’t have someone come in and ask a question about filling out an online form, then isolate them in a little box for like 5 hours before we get down to business.

In order to actually work and be useful, AI needs to understand the way people talk, write, and think. It needs to understand all that better than most people do.

Books are probably one of the faster ways for an AI to learn language, not only language, but the nuanced ways people say things. Especially with endless books in endless languages available, self-pub books, all sorts of things that not only instruct an AI in the ways we intentionally communicate,

but also in the ways we unintentionally tell people things.

Feed books in, the AI absorbs not just the information, but the ways we communicate.

And that…I don’t hate that.

I think AI is very likely to be able to help us do a lot of things more quickly, which would aid in advancement in a lot of places it REALLY counts.

I think, for example, AI skin cancer detection would be wonderful. If people can basically prop up their phones and let the camera take a gander (minus the horrific security concerns here, but let’s leave that be for a moment), I’m betting we would have a lot more people actually getting regular screenings than we do now, what with a wait time to see a dermatologist, the expense of a visit, all that stuff. If it worked, that’d be pretty sweet.

Our water heater broke. It’d be pretty awesome to be able to take a short video, submit it to an AI, and to have the problem diagnosed in seconds. We’re waiting until Tuesday for a plumber to come over. I haven’t showered since Friday. I don’t like to make mountains of molehills, but there is a definite mountain of stank on the mons pubis, know what I mean?

I’m not suggesting this is perfect or a great idea today, but an application of AI that I really think would be of bigtime benefit, and something that most of us would appreciate when we’re in a bad spot.

I don’t think many among us are against the idea of AI making medical diagnoses fast, cheap, easy and effective. Getting an important diagnosis as early as possible might be the key to a better outcome. This wouldn’t replace a doctor, just supplement one. It wouldn’t replace someone actually hooking up a new water heater, just give me a better idea of how likely it is that I need to buy a new one versus having someone attempt a repair.

And I think this is pretty close to what AI companies are arguing: The good of progress outweighs the bad of potential copyright infringement.

What The Other Side is Arguing

AI companies should pay for their copies of the books.

First of all, yeah, duh.

If we’re comparing AI learning to human learning and saying that humans learn by reading and imitating authors, well, it’d be kind of insane to justify book piracy, stealing copies of books, because we were writing books ourselves. Movie piracy? Oh, no, your honor, I’m a filmmaker myself. See this clip of my cat sticking out its leg dramatically in order to lick its asshole? How am I supposed to make stuff like this without stealing The Criterion Collection?

I mean, come on, fuckers, you have BILLIONS, you’re telling me you can’t afford The Complete Works of Shakespeare, a book every English major probably buys at least twice in a lifetime ON AN ENGLISH MAJOR’S SALARY!?

Another sticking point for the publishers and authors, a Fair Use argument only applies when the person violating copyright admits that what they were doing is violating copyright, which means admitting to wrongdoing. Fair Use is an acknowledgement that copyright has been broken, but for a good reason.

A classroom teacher showing a movie is likely a reasonable use of something, even if they can’t clear the copyright in an official way, because it’s for educational purposes, it’s in a closed classroom setting, there’s no money exchanged, it’s unlikely affecting the market for the movie…for a lot of reasons.

And it seems that the AI companies do not want to admit that this is a copyright violation and to then justify it via the application. And they don’t want to do that because their applications are not good-faith efforts that’d fall under the umbrella of First Amendment rights (AIs do not have those…at this time), education, criticism, commentary.

AI companies aren’t training their machines to do those things. They are training them to make money.

And the application of letting an AI write a David Baldacci-esque thriller is not reasonable Fair Use.

Baldacci Is Right, Just Like Metallica

David Baldacci talked to Congress about AI, and although the folks questioning him focused mostly on whether Baldacci’s rights were being violated, I think Baldacci actually brought up something far more important, something we need to consider in terms of the future of human creativity:

It’s no secret that the publishing industry relies on whales like Baldacci to bring in bucks, and they can then use some of those dollars to put out other books that are not necessarily safe bets. With the extra cash a Baldacci brings in, a publisher can take chances on new authors, put out books that they believe in, even if they’re not sure they can make their money back.

This is how authors, today’s megastars, all got their start: A publisher had enough money from publishing bestsellers to take a chance on someone else.

At a book conference, I once heard someone who worked in publishing say, essentially, that they don’t really love putting out memoirs by celebrities, but they make money, and that allows the publishers to put out other books.

When you’re wondering why a publisher is putting out the fifth memoir by someone who can’t possibly have multiple books’ worth of interesting things to say

it’s because they sell, and when a book sells, it gives the publisher more room to publish things that are less bankable.

Baldacci’s concern is that AI, in destroying his financial value, destroys the financial structure of publishing, and therefore destroys any opportunity for any new writers to break through.

And I think he’s 100% right.

Just like Metallica

I’m old enough to remember similar arguments when Napster and Metallica went at it, and a lot of the reactions among the public were like: Metallica is rich as hell, who cares if their music is pirated?

But maybe it wasn’t just about Metallica fattening their wallets. Because, indeed, Napster wasn’t going to kill Metallica.

Napster might have killed bands that could’ve opened for Metallica, though. It might’ve killed bands that never got out of the garage.

Because a record company couldn’t make as much money from Metallica as they once did, they operated with diminished opportunities to take risks.

Is that why music became bland? Because labels couldn’t afford to take risks, so they had to go with the same sure things? Is this why radio became so boring? Because they had to play the same dozen songs, over and over, because they knew people might get sick of them, but at least they wouldn’t change the station?

I don’t know, we can’t really know. But it’s entirely possible.

And Baldacci, I guess being the Metallica of publishing in this moment (weird comparison, I bet nobody else is connecting those two dots), is in the Metallica seat when it comes to this somewhat-similar situation.

Baldacci is fine. Personally, I’m sure he’s done quite well. He must be quite prominent if Congress is asking him to testify on the matter.

But if the Baldaccis, the Kings, the Kingsolvers, the Suzanne Collins-es of the world are devalued, it destroys the ability of the publishing machine to publish, well, much of anything new.

It’s not just about money going out of Baldacci’s pocket, it’s about publishing being destroyed and never again reading another book by a human author.

Or, maybe, slightly less of a problem, it’s about publishers not being able to take a chance, so we get A WHOLE LOT MORE of what we’ve already seen, very little that’s new and interesting.

Metallica was presenting a non-hypothetical: Here’s how we lose money. Here are the effects of that.

Baldacci is doing the same.

And it seems the AI company responses are purely hypothetical. “Here is what AI might be able to do, someday.”

It’s the extinguishment of possibility that chafes. It’s closing a door to a future with new, different, interesting, fun books. It’s removing “author” as an occupation.

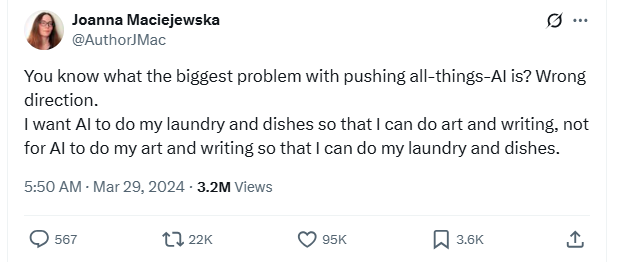

Writing books falls pretty firmly into the category of things we would rather do, that we’d like more time to focus on while an AI does the laundry and dishes.

Solutions Pete

I think the ingestion of materials is probably okay, or at the least, justified by the AI’s need to learn language.

For me, it’s less about ingestion of material, and I suspect that’s how authors feel about it, too. My suspicion is that they’re attacking the ingestion side because it’s the more clear-cut violation of law.

But let’s talk output.

I don’t necessarily see why the need to ingest lots of material means any person should be able to get ChatGPT to output an entire novel in the style of David Baldacci.

To me, this seems like the technological equivalent of a copy machine in that it’s duplicating something, making an additional copy. It’s not an exact copy, but it’s close, and it’s not differentiated for artistic or parodic reasons.

For me, this is where the AI companies’ arguments fall very, very short: I think the ingestion is possibly justified by the potential of AI, but I don’t see why this ingestion also requires allowing an AI to output an entire novel in the style of another author.

The REAL Answer

AI companies, I implore you:

Allow your AI to write novels in anyone’s style. But when this type of request is made, ROYALLY fuck up the ending.

Make people read 320-ish pages only to get to an ending that fails spectacularly when it comes time to stick the landing.

THIS, this is the simplest, cleanest way to handle it. If the endings of AI novels are fucked, nobody is going to read that shit for fear of investing time in something that super sucks.